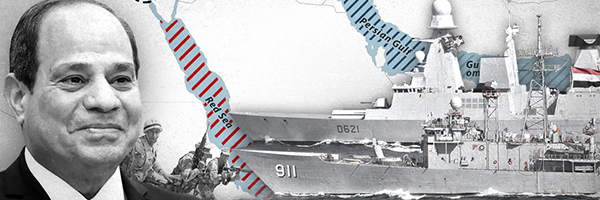

Why is Egypt’s Navy commanding a NATO-led coalition in the Red Sea?

The Cradle, January23, 2023 — In recent years Egypt has been developing and strengthening its navy in and around the Red Sea, but this is arguably part of a broader US strategy for the region.

The Cradle, January23, 2023 — In recent years Egypt has been developing and strengthening its navy in and around the Red Sea, but this is arguably part of a broader US strategy for the region.

On 12 December 2022, the Egyptian Navy took over command of the newly established Combined Task Force 153 (CTF 153) from the US Navy.

CTF 153 is responsible for controlling maritime traffic in the Red Sea and is the fourth unit of the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF), an international coalition established in 2001 by the US and its NATO allies which is concentrated in West Asia’s waterways – from the Persian Gulf to the Suez Canal.

In addition to CTF 153, the CMF includes three other fleets: The CTF 150, which operates “outside the Persian Gulf” in the Sea of Oman; The CTF 151, which specializes in “combating piracy;” and the CTF 152, which operates in Persian Gulf waters. The coalition is considered an arm of NATO and is led by an American officer who commands the US Fifth Fleet, headquartered in Bahrain.

Impact of the war in Ukraine

The establishment of this alliance and its four units reflects a change in US security policy at sea: instead of US forces taking sole responsibility for protecting sea lanes, the Pentagon will partner with regional allies to secure waterways.

Egypt’s command of CTF 153 in the Red Sea represents a new political positioning for Cairo, raising concerns about potential conflicts with Iran, direct Egyptian involvement in the Yemeni war, and possible tensions with Russia and China.

It is important to view this decision in context of the ongoing Russian-NATO conflict on Ukrainian soil, which has significantly impacted international relations and military alliances over the past 11 months.

Moscow’s Special Military Operation in Ukraine has effectively ended the Helsinki Agreement of 1975, which established principles for relations between western and eastern Europe, such as respect for national sovereignty, border immunity, territorial integrity, and the peaceful resolution of disputes.

In an effort to restore Russia as a leading global power, Russian President Vladimir Putin may be aspiring to return to the Yalta system, which is based on sharing “spheres of influence” and limited sovereignty of dependent states, according to the Brezhnev principle.

Contrary to western expectations, the first year of the war has demonstrated that Russia is not isolated, and is capable of replacing European and western commercial partners with others in the short and medium term. China and India, for example, are replacing Europe as a market for Russian gas and oil.

However, the continued tightening of trade and financial sanctions in the long run is likely to place Moscow in a difficult position, particularly in obtaining western technological components. This could lead to Russia vigorously activating its partnerships with its allies around the world, creating further schisms between the two global poles.

What is Egypt’s position and role in all of this?

With the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the US recognized the need for a new security policy in the Mediterranean and Red Seas to secure its decades-long advantageous position in the region.

It was also necessary to improve relations with Arab countries -especially those in the Persian Gulf – which had deteriorated in the wake of the Joe Biden presidency.

On 15 July, 2022, Biden visited Saudi Arabia for the Jeddah Security and Development Summit, where he met with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, leaders of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Iraq, and Jordan, as well as Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi.

At the summit, he emphasized that the US “will not abandon” West Asia and will not leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia, or Iran, while recognizing the need to allow greater autonomy for its Arab allies, now led by a new generation of leaders.

The events of the past year, including increased military activity from Russia and growing conflict with China, have led to renewed western efforts to unite the US and Europe, bolster NATO, and mobilize allies in the so-called “democratic world” against “authoritarian states.”

The Red Sea region and key maritime chokepoints, such as the Suez Canal, Bab al-Mandab, and the Strait of Hormuz, have become increasingly important due to this global power competition amid ongoing instability in West Asia and North Africa.

The Bab al-Mandab Strait, in particular, is a critical point for navigation through the Suez Canal, and is of vital strategic value to Egypt and the global economy. The 30 kilometers-wide strait is the shortest route linking the Indian Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Atlantic Ocean. It is also a key transit point for oil exports from the Arabian Peninsula and Persian Gulf.

Due to these factors, Egypt has taken steps to develop its naval capabilities and has asserted its right to militarily intervene to protect the security of the strait.

Referencing the war in Yemen, President Sisi boldly says: “Egypt has the right to intervene militarily to prevent the Houthis from controlling or closing the strait,” because that “would have negative effects on trade in the Strategic Suez Canal,” the main source of income for the country.

To date, despite the Saudi-led coalition’s military losses, Egypt has not deployed ground forces to support the war efforts. It did, however, send four warships to the Bab al-Mandab in May 2015 to underline the point.

Cairo bolsters its naval presence

In recent years, Cairo has been urged by Washington to enhance its naval capabilities in West Asia and North Africa. The discovery of natural gas fields in those regions, and the absence of a reliable “American protector” during the Donald Trump administration, has led to intense competition among coastal countries for access to these resources.

Tensions between Turkiye and Egypt have revived historical rivalries and escalated into a naval arms race in the eastern Mediterranean. This, is in addition to the deteriorating security situation in the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa, and the transformation of the Red Sea coast into a center for international military bases, such as in Djibouti, Eritrea, and Somalia.

For deterrence purposes, and to ensure greater control over its strategic infrastructure and protect its offshore energy platforms, Cairo began developing its maritime capabilities and equipping itself with a fleet capable of operating outside its territorial waters – from the western Mediterranean to the Bab al-Mandab Strait.

The main pillars of this program include expanding military infrastructure and building new Egyptian naval bases at some strategic points, such as the “Bernice Naval Base” near the Sudanese border and the “Ras Jarqub” base on the Mediterranean Sea, near the Libyan border.

Between 2014 and 2015, Egypt developed its fleet with the addition of US Knox frigates and Spanish Discoberta corvettes. It also purchased two amphibious assault helicopter carriers (Mistral) and four French-made Godwind multi-role cruisers, with an agreement to transfer industrial knowledge to Egypt’s shipbuilding industry. The cruisers were equipped with MICA anti-aircraft missiles and Exocet MM40 anti-ship missiles.

In 2019, Egypt procured four MEKO A-200EN frigates from Germany, a coastal patrol vessel, and TNC 35 and FPB 38 patrol boats. In 2020, it purchased two FREM units and 32 medium helicopters from Italy, and four diesel-electric submarines from Germany of the 209 1400mod model.

This strengthening of the Egyptian Navy has also led to its inclusion in the aforementioned CMF and leadership of CTF 153. However, it is unclear whether this new positioning of the Egyptian navy – in partnership with the US – is geared to direct conflict with Iran in the Red Sea or to cause fissures with Egypt’s Russian and Chinese partners at sea.

US influence in shaping Egypt’s maritime security

According to Egyptian geopolitical researcher Ahmed Maulana, “the presence of allies for Washington in the Red Sea and the Mediterranean region is very important to the US security strategy that was announced in October 2022.”

“American military forces have the right to cross the Suez Canal 48 hours after informing the Egyptian administration, while Cairo requires other countries to submit a request for passage 60 days in advance. The United States is the only country that has been exempted from these procedures, which gives its forces an advantage in the speed of movement and deployment.”

The new US security strategy asserts that “the spot of conflict in the next ten years will be with China in the Pacific and Indian oceans.” Despite the war in Ukraine and skirmishes in several regions, Washington believes that China is the only country genuinely capable of challenging US hegemony and reshaping the world order.

For this reason, Maulana thinks “the United States is seeking to mobilize its capabilities in these two areas, and is working to strengthen various military partnerships with Australia, India, the Philippines, South Korea and Japan.”

The importance of the Mediterranean and the Red Seas for this strategy, he says, lies in the fact that they are:

“The fastest route for the movement of American forces from the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar, then the Mediterranean Sea, passing through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea, to the Indian and Pacific oceans.”

The Arab-US-Israel axis

The US has shifted its strategy in the Indian and Pacific Oceans by reducing direct military involvement in certain areas and supporting alliances formed by its regional allies.

For instance, Israel has been transferred from the US European Command umbrella to the US Central Command (whose operational theater spans 21 nations, from North Africa, to West, Central, and South Asia). The controversial switch was made to establish a missile and air defense umbrella between Israel, the Gulf states, Egypt, and Jordan against potential conflicts with Iran.

This coordination and agreements with Israel pave the way for an Arab-US-Israeli axis, wherein Washington supplies the axis with intelligence and weapons while minimizing the direct involvement of US troops in conflict – a strategy learned from mistakes in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Maulana, however, insists that the possibility of Egypt entering into a conflict between the major powers is “very remote.” Cairo “is keen to play on the three conflicting axes to produce benefits, and the naval role played by Egypt is not new, but rather goes back several decades.”

Maulana also explains why a clash between regional players in these waterways is unlikely: “The Houthis, for example, do not possess a significant naval force that requires corresponding armament, while Iran does not dare to directly obstruct navigation in the Bab al-Mandab.”

Enhancing Egypt’s naval capabilities can therefore be viewed as an effort to increase Cairo’s weight and establish deterrence in a region rife with conflicts, in which neighboring countries in both West Asia and North Africa are armed with astronomical military budgets.

The question is whether Washington has the intent or ability to activate its Egyptian naval partner to fight conflicts on its behalf – and whether Cairo will accept that role willingly.