What Spearheaded 22 Years of War and Atrocities? Unocal and the Coveted Trans-Afghan Pipeline Route

October 7, 2023 marks the commemoration of the US – NATO invasion of Afghanistan on October 7, 2001.

Twenty-two Years of War and Atrocities have been spearheaded by

- the geopolitics of the strategic trans-Afghan pipeline, which is the object of this article,

- the Taliban’s decision (2000) to drastically curtail opium production with a view to cancelling outright the multibillion Afghan drug trade.

September 11, 2001 provided the justification to wage war on Afghanistan. A war cabinet was created at 11 o’clock at night on September 11, 2001. On the following day, NATO’s North Atlantic Council met in Brussels.

An unnamed foreign power had attacked America allowing the nation under attack, to strike back in the name of “self-defense”.

“if it is determined that the [September 11, 2001] attack against the United States was directed from abroad [Afghanistan] against “The North Atlantic area“, it shall be regarded as an action covered by Article 5 of the Washington Treaty”. (emphasis added)

The bombing and invasion of Afghanistan which commenced on October 7, 2001 was described as a “campaign” against “Islamic terrorists”, rather than a war.

America’s “War on Terrorism” was born on September 11, 2001.

Michel Chossudovsky, August 30, 2023

***

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Argentine oil company Bridas, led by its ambitious chairman, Carlos Bulgheroni, became the first company to exploit the oil fields of Turkmenistan and propose a pipeline through neighboring Afghanistan. A powerful US-backed consortium intent on building its own pipeline through the same Afghan corridor would oppose Bridas’ project.

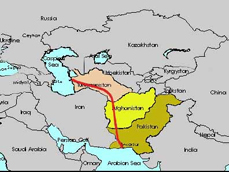

The Coveted Trans-Afghan Route

Upon successfully negotiating leases to explore in Turkmenistan, Bridas was awarded exploration contracts for the Keimar block near the Caspian Sea, and the Yashlar block near the Afghanistan border. By March 1995, Bulgheroni had accords with Turkmenistan and Pakistan granting Bridas construction rights for a pipeline into Afghanistan, pending negotiations with the civil war-torn country.

Upon successfully negotiating leases to explore in Turkmenistan, Bridas was awarded exploration contracts for the Keimar block near the Caspian Sea, and the Yashlar block near the Afghanistan border. By March 1995, Bulgheroni had accords with Turkmenistan and Pakistan granting Bridas construction rights for a pipeline into Afghanistan, pending negotiations with the civil war-torn country.

The following year, after extensive meetings with warlords throughout Afghanistan, Bridas had a 30-year agreement with the Rabbani regime to build and operate an 875-mile gas pipeline across Afghanistan.

Bulgheroni believed that his pipeline would promote peace as well as material wealth in the region. He approached other companies, including Unocal and its then-CEO, Roger Beach, to join an international consortium.

But Unocal was not interested in a partnership. The United States government, its affiliated transnational oil and construction companies, and the ruling elite of the West had coveted the same oil and gas transit route for years.

A trans-Afghanistan pipeline was not simply a business matter, but a key component of a broader geo-strategic agenda: total military and economic control of Eurasia (the Middle East and former Soviet Central Asian republics). Zbigniew Brezezinski describes this region in his book “The Grand Chessboard-American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives” as “the center of world power.” Capturing the region’s oil wealth, and carving out territory in order to build a network of transit routes, was a primary objective of US military interventions throughout the 1990s in the Balkans, the Caucasus and Caspian Sea.

A trans-Afghanistan pipeline was not simply a business matter, but a key component of a broader geo-strategic agenda: total military and economic control of Eurasia (the Middle East and former Soviet Central Asian republics). Zbigniew Brezezinski describes this region in his book “The Grand Chessboard-American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives” as “the center of world power.” Capturing the region’s oil wealth, and carving out territory in order to build a network of transit routes, was a primary objective of US military interventions throughout the 1990s in the Balkans, the Caucasus and Caspian Sea.

As of 1992, 11 western oil companies controlled more than 50 percent of all oil investments in the Caspian Basin, including Unocal, Amoco, Atlantic Richfield, Chevron, Exxon-Mobil, Pennzoil, Texaco, Phillips and British Petroleum.

In “Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia” (a definitive work that is a primary source for this report), Ahmed Rashid wrote,

“US oil companies who had spearheaded the first US forays into the region wanted a greater say in US policy making.”

Business and policy planning groups active in Central Asia, such as the Foreign Oil Companies Group operated with the full support of the US State Department, the National Security Council, the CIA and the Department of Energy and Commerce.

Among the most active operatives for US efforts: Brzezinski (a consultant to Amoco, and architect of the Afghan-Soviet war of the 1970s), Henry Kissinger (advisor to Unocal), and Alexander Haig (a lobbyist for Turkmenistan), and Dick Cheney (Halliburton, US-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce).

Among the most active operatives for US efforts: Brzezinski (a consultant to Amoco, and architect of the Afghan-Soviet war of the 1970s), Henry Kissinger (advisor to Unocal), and Alexander Haig (a lobbyist for Turkmenistan), and Dick Cheney (Halliburton, US-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce).

Unocal’s Central Asia envoys consisted of former US defense and intelligence officials. Robert Oakley, the former US ambassador to Pakistan, was a “counter-terrorism” specialist for the Reagan administration who armed and trained the mujahadeen during the war against the Soviets in the 1980s. He was an Iran-Contra conspirator charged by Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh as a key figure involved in arms shipments to Iran.

Richard Armitage, the current Deputy Defense Secretary, was another Iran-Contra player in Unocal’s employ. A former Navy SEAL, covert operative in Laos, director with the Carlyle Group, Armitage is allegedly deeply linked to terrorist and criminal networks in the Middle East, and the new independent states of the former Soviet Union (Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrghistan).

Armitage was no stranger to pipelines. As a member of the Burma/Myanmar Forum, a group that received major funding from Unocal, Armitage was implicated in a lawsuit filed by Burmese villagers who suffered human rights abuses during the construction of a Unocal pipeline. (Halliburton, under Dick Cheney, performed contract work on the same Burmese project.)

Bridas Versus the New World Order

Much to Bridas’ dismay, Unocal went directly to regional leaders with its own proposal. Unocal formed its own competing US-led, Washington-sponsored consortium that included Saudi Arabia’s Delta Oil, aligned with Saudi Prince Abdullah and King Fahd. Other partners included Russia’s Gazprom and Turkmenistan’s state-owned Turkmenrozgas.

John Imle, president of Unocal (and member of the US-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce with Armitage, Cheney, Brezezinski and other ubiquitous figures), lobbied Turkmenistan’s president Niyazov and prime minister Bhutto of Pakistan, offering a Unocal pipeline following the same route as Bridas.’

Dazzled by the prospect of an alliance with the US, Niyazov asked Bridas to renegotiate its past contract and blocked Bridas’ exports from Keimar field. Bridas responded by filing three cases with the International Chamber of Commerce against Turkmenistan for breach of contract. (Bridas won.) Bridas also filed a lawsuit in Texas charging Unocal with civil conspiracy and “tortuous interference with business relations.” While its officers were negotiating with Pakistani and Turkmen oil and gas officials, Bridas claimed that Unocal had stolen its idea, and coerced the Turkmen government into blocking Bridas from Keimir field. (The suit was dismissed in 1998 by Judge Brady G. Elliott, a Republican, who claimed that any dispute between Unocal and Bridas was governed by the laws of Turkmenistan and Afghanistan, rather than Texas law.)

In October 1995, with neither company in a winning position, Bulgheroni and Imle accompanied Niyazov to the opening of the UN General Assembly. There, Niyazov awarded Unocal with a contract for a 918-mile natural gas pipeline. Bulgheroni was shocked. At the announcement ceremony, Unocal consultant Henry Kissinger said that the deal looked like “the triumph of hope over experience.”

Later, Unocal’s consortium, CentGas, would secure another contract for a companion 1,050-mile oil pipeline from Dauletabad through Afghanistan that would connect to a tanker loading port in Pakistan on the coast of the Arabian Sea.

Although Unocal had agreements with the governments on either end of the proposed route, Bridas still had the contract with Afghanistan.

The problem was resolved via the CIA and Pakistani ISI-backed Taliban. Following a visit to Kandahar by US Assistant Secretary of State for South Asia Robin Raphael in the fall of 1996, the Taliban entered Kabul and sent the Rabbani government packing.

Bridas’ agreement with Rabbani would have to be renegotiated.

Wooing the Taliban

According to Ahmed Rashid, “Unocal’s real influence with the Taliban was that their project carried the possibility of US recognition, which the Taliban were desperately anxious to secure.”

Unocal wasted no time greasing the palms of the Taliban. It offered humanitarian aid to Afghan warlords who would form a council to supervise the pipeline project. It provided a new mobile phone network between Kabul and Kandahar. Unocal also promised to help rebuild Kandahar, and donated $9,000 to the University of Nebraska’s Center for Afghan Studies. The US State Department, through its aid organization USAID, contributed significant education funding for Taliban. In the spring of 1996, Unocal executives flew Uzbek leader General Abdul Rashid Dostum to Dallas to discuss pipeline passage through his northern (Northern Alliance-controlled) territories.

Bridas countered by forming an alliance with Ningarcho, a Saudi company closely aligned with Prince Turki el-Faisal, the Saudi intelligence chief. Turki was a mentor to Osama bin Laden, the ally of the Taliban who was publicly feuding with the Saudi royal family. As a gesture for Bridas, Prince Turki provided the Taliban with communications equipment and a fleet of pickup trucks. Now Bridas proposed two consortiums, one to build the Afghanistan portion, and another to take care of both ends of the line. By November 1996, Bridas claimed that it had an agreement signed by the Taliban and Dostum—trumping Unocal.

The competition between Unocal and Bridas, as described by Rashid, “began to reflect the competition within the Saudi Royal family.”

In 1997, Taliban officials traveled twice to Washington, D.C. and Buenos Aires to be wined and dined by Unocal and Bridas. No agreements were signed.

It appeared to Unocal that the Taliban was balking. In addition to royalties, the Taliban demanded funding for infrastructure projects, including roads and power plants. The Taliban also announced plans to revive the Afghan National Oil Company, which had been abolished by the Soviet regime in the late 1970s.

Osama bin Laden (who issued his fatwa against the West in 1998) advised the Taliban to sign with Bridas. In addition to offering the Taliban a higher bid, Bridas proposed an open pipeline accessible to warlords and local users. Unocal’s pipeline was closed—for export purposes only. Bridas’ plan also did not require outside financing, while Unocal’s required a loan from the western financial institutions (the World Bank), which in turn would leave Afghanistan vulnerable to demands from western governments.

Bridas’ approach to business was more to the Taliban’s liking. Where Bulgheroni and Bridas’ engineers would take the time to “sip tea with Afghan tribesmen,” Unocal’s American executives issued top-down edicts from corporate headquarters and the US Embassy (including a demand to open talks with the CIA-backed Northern Alliance).

While seemingly well received within Afghanistan, Bridas’ problems with Turkmenistan (which they blamed on Unocal and US interference) had left them cash-strapped and without a supply.

In 1997, they went searching for a major partner with the clout to break the deadlock with Turkmenistan. They found one in Amoco. Bridas sold 60 percent of its Latin American assets to Amoco. Carlos Bulgheroni and his contingent retained the remaining minority 40 percent. Facilitating the merger were other icons of transnational finance, Chase Manhattan (representing Bridas), Morgan Stanley (handling Amoco) and Arthur Andersen (facilitator of post-merger integration). Zbigniew Brezezinski was a consultant for Amoco.

(Amoco would merge with British Petroleum a year later. BP is represented by the law firm of Baker & Botts, whose principal attorney is James Baker, lifelong Bush friend, former secretary of state, and a member of the Carlyle Group.)

Recognizing the significance of the merger, a Pakistani oil company executive hinted, “If these (Central Asian) countries want a big US company involved, Amoco is far bigger than Unocal.”

Clearing the Chessboard Again

By 1998, while the Argentine contingent made slow progress, Unocal faced a number of new problems.

Gazprom pulled out of CentGas when Russia complained about the anti-Russian agenda of the US. This forced Unocal to expand CentGas to include Japanese and South Korean gas companies, while maintaining the dominant share with Delta.

Human rights groups began protesting Unocal’s dealings with the brutal Taliban. Still riding years of Clinton bashing and scandal mongering, conservative Republicans in the US attacked the Clinton administration’s Central Asia policy for its lack of clarity and “leadership.”

Once again, violence would change the dynamic.

In response to the bombing of US embassies in Nairobi and Tanzania (attributed to bin Laden), President Bill Clinton sent cruise missiles into Afghanistan and Sudan. The administration broke off diplomatic contact with the Taliban, and UN sanctions were imposed.

Unocal withdrew from CentGas, and informed the State Department “the gas pipeline would not proceed until an internationally recognized government was in place in Afghanistan.” Although Unocal continued on and off negotiations on the oil pipeline (a separate project), the lack of support from Washington hampered efforts.

Meanwhile, Bridas declared that it would not need to wait for resolution of political issues, and repeated its intention of moving forward with the Afghan gas pipeline project on its own. Pakistan, Turkmenistan and Afghanistan tried to push Saudi Arabia to proceed with CentGas (Delta of Saudi Arabia was now the leader). But war and US-Taliban tension made business impossible.

For the remainder of the Clinton presidency, there would be no official US or UN recognition of Afghanistan. And no progress on the pipeline.

Then George Walker Bush took the White House.