In Gaza, The West Has Succumbed to a Racist Fantasy

Kolya Roy Ludwig, Orinoco Tribune, October 20, 2023

Kolya Roy Ludwig, Orinoco Tribune, October 20, 2023

“This is a struggle between the children of light and the children of darkness, between humanity and the law of the jungle.” – Benjamin Netanyahu

“The crime of the Palestinians is that they keep reappearing, refusing to die in silence and eventually breaching the fence of besieged Gaza.” – Emile Badarin

Todd McGowan’s 2022 book ‘The Racist Fantasy: Unconscious Roots of Hatred’ lays out a framework that is indispensable for understanding Israel’s latest campaign of brutality against the Palestinians. McGowan’s argument departs from common understandings of racism, which identify it only as an ideological phenomenon or as an oppressive social relation, without accounting for the libidinal force that drives it—namely, the racist fantasy.

Fantasy brings ideology to life. Without a racist fantasy, racist ideology, by itself, could not account for the excessiveness of colonial violence, nor the atrocities we are witnessing in Gaza today.

The racist fantasy, like all fantasy, emerges to cover over some trauma that we have difficulty facing head on. For Israel and for America, the trauma we confront is, in part, the failure of our societies to produce the satisfaction promised by our national myths. We are haunted by this failure, and its persistence despite all attempts to construct a scapegoat to blame for it. No matter how many victories we claim against imagined enemies or threats, Western subjects are confronted by the fact that we are merely flawed people facing an existential crisis like everyone else.

The difficulty of accepting the fundamental fact of alienation establishes the basis for the racist fantasy. In this fantasy, we shift the blame for our own alienation onto the racial other. By establishing the racial other as the obstacle in our fantasy, we accomplish two things: (1) we keep the object of desire—i.e. a life of genuine satisfaction and fulfillment—at a distance, always on a horizon that is blocked by the imagined transgressions of the racial other; and (2) we imagine that the racial other has already gained access to the enjoyment we seek, driving us mad with envy, and giving us the energy to structure a whole society around this fantasy.

The white supremacist fantasy is open to all who seek the sense of belonging that it promises. This is why a so-called Jewish state—its own subjects the historic targets of white supremacy—can participate in the white supremacist project by proclaiming the superiority of Western values and violently subjugating a population that white supremacy has turned its attention to as the primary racial target of the day. Many Israeli citizens, though, are about to discover that there is never a point at which the belonging promised by white supremacy actually delivers its anticipated rewards. The extent of the disappointment will only become more apparent after Israel’s excessive bombing campaign against Gaza and the violent raids on the West Bank. The doubling down of the addict on their object of indulgence only calls more attention to the void.

Key to the vitality of the racist fantasy is its insatiability; no matter how many Palestinians Israel slaughters, the imagined Arab terrorist still lurks within a different apartment tower, or school, or hospital, that must also be razed to the ground. The more Israel bombs Gaza, the more its ire is inflamed at the images of Palestinian life that still emerge. This is the most difficult part of the fantasy to accept: Israel envies the marginality of the Palestinian people. There is no enjoyment in the white supremacist project except through the marginalized racial other, and that enjoyment represents an existential threat to the racist who cannot access it directly. Many poets, filmmakers, and historians have made this observation (several of whom are powerfully invoked in McGowan’s book); it is not unique to psychoanalytic theory. Consequently, the more marginal the bombing campaign makes their enemy, the more enjoyment Israelis perceive that enemy gaining access to. This enrages the occupier even more, and the bombing campaign intensifies. There is no limit to the aggression demanded by the racist fantasy.

The extent of the imagined threat is revealed in the recent false claims about the rape of Israeli women and the beheading of Israeli babies by Palestinian fighters. While these claims have been debunked, they accurately reflect the scale of the threat perceived by the racist subject. This is why Israeli president Isaac Herzog is being sincere when he says “there are no innocents in the Gaza Strip.”

Because we in the West have been deputized in the same anti-Arab fantasy as the settlers in Israel, I fear that even with social media’s ability to show exactly what’s happening to Palestinians in Gaza today, the horrific images may not be enough to quell Western support for the atrocities (and may even have the opposite effect). Despite the passage of time since 9/11, and the murderous wars we supported throughout the Middle East and North Africa since then, we have learned nothing from our past. We are absolutely caught up in its legacy. We haven’t confronted our failures as a society, nor the fact of our alienation as subjects—traumas which cannot be blamed on any imagined racial other. The anti-Arab fantasy, despite the emergence of other racist fantasies to de-center it (for a time), can always resurface because we have not confronted the reasons for its hold over us.

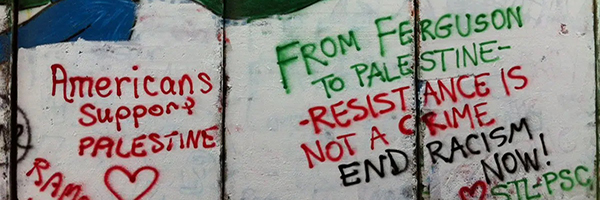

What is the answer, then? Solidarity. Solidarity is the shared experience of facing our alienation as human beings, and not escaping from this alienation through a racist fantasy. Solidarity must take a political form, however, because sentiment is not enough to overcome the power of the white supremacist project. The answer to the depraved Western project is an organized political response which presents an alternative project that is rooted in solidarity. This is the project we must take up as Western subjects whose fantasmatic investment in our governments’ crimes is what makes them possible.

*

Kolya Roy Ludwig is a former community college instructor of psychology, and an organizer with the People’s Education Program and All Power Books in Los Angeles, California.