Aid to Ukraine: The Administration Requests More Money and Faces Political Battles Ahead

This report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) (an establishment think tank) presents relevant information and analysis on the billions of dollars of so-called “U.S. Aid to Ukraine”, a large percentage of which is diverted to The Depart of Defense, (which transfers funds to The US Army, US Air Force, US Navy), several departments of the U.S. administration including the State Department, The Department of Health and Human Services, as well as The World Bank, in support of loan activities which are totally unrelated to Ukraine, in support of “the IDA’s crisis response window, which provides rapid financing and grants to the poorest countries to respond to severe crises”.

Quotations from the report:

Thus, “aid to Ukraine” is a misnomer since 40 percent does not go to Ukraine itself. However, all is related to the war.”

“The great fear is a “forever war,” a conflict that goes on indefinitely at a great human and fiscal cost but without a clear outcome.”

Michel Chossudovsky, Global Research, August 23, 2023

***

Emphasis added by Global Research.

***

President Biden has asked Congress for an additional $24 billion for the war in Ukraine, bringing the total aid to $135 billion.

Such aid is critical, not just for military operations but for easing the war’s humanitarian impact. [according to CISIS]

Although most of this request tracks with previous requests, some items are only tangentially related to the war in Ukraine. Furthermore, this request will likely engender more debate than previous requests as concerns about a “forever war” build. Although the administration will likely prevail this time, the next request― which is inevitable―may face a more difficult reception.

Q1: What is in the request?

A1: The $24 billion request for Ukraine aid is part of a larger $40 billion supplemental that also includes domestic disaster relief and border security.

The Ukraine request includes money for both the Department of Defense (DOD) ($13.2 billion) and the Department of State ($10.7 billion), with small amounts going to the Department of Health and Human Services ($100 million) and the Department of Energy ($65 million).

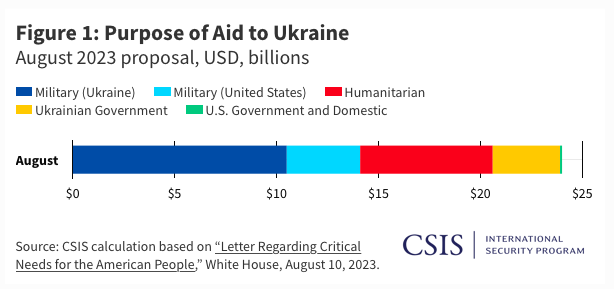

Figure 1 below shows the purpose of the funding. Although attention has focused on military aid (“Military [Ukraine]”), funds for the Ukrainian government to continue regular governmental operations (“Ukrainian Government”) and humanitarian aid (“Humanitarian”) are also significant.

Further, the DOD has received money for its increased military activity in Eastern Europe and for acceleration of munitions production (“Military [United States]”). Most of this goes to the U.S. Army, with lesser amounts to the U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force. Finally, other parts of the U.S. government have received money for activities related to the war such as nonproliferation efforts (“U.S. Government and Domestic”). Thus, “aid to Ukraine” is a misnomer since 40 percent does not go to Ukraine itself. However, all is related to the war.

One striking element of the request is that $3.5 billion is, at best, indirectly related to Ukraine and arguably entirely unrelated.

One striking element of the request is that $3.5 billion is, at best, indirectly related to Ukraine and arguably entirely unrelated.

The Department of State would receive $1 billion for “transformative, quality, and sustainable infrastructure projects that align with U.S. strategic interests and support U.S. partners and allies. Funding would allow the United States to provide credible, reliable alternatives to out-compete China.”

The World Bank through the International Development Association would receive $1 billion “to support the IDA’s crisis response window, which provides rapid financing and grants to the poorest countries to respond to severe crises” and another $1.25 billion through the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development for loan guarantees “to provide financing to help countries such as Colombia, Peru, Jordan, India, Indonesia, Morocco, Nigeria, Kenya, and Vietnam build new infrastructure and supply chains.” Finally, $200 million would go to a new fund in the Department of State to counter “Russian malign actors” in Africa.

While all of these uses might be justified, their inclusion in an emergency supplemental was likely opportunistic. The Office of Management and Budget often refers to this as the “Christmas tree” effect, whereby agencies that could not get money through the regular budget try to append the funds to an emergency supplemental.

Q2: Why did this request appear now?

A2: Congress has appropriated a total of $111 billion as a result of the conflict, which was intended to last through the end of the fiscal year (September 30). Because the money will run out soon, the administration needs to ask for more now to give the appropriations process time to play out.

Outside aid is vital for Ukrainian resistance. Militaries in active combat require a constant flow of weapons, munitions, and supplies. Without outside military aid, Ukrainian resistance would collapse in two or three weeks. Thus, the United States, with its allies and partners, needs to provide an uninterrupted flow of military aid. Even a short gap in support would badly undermine Ukrainian resistance. The same is true of humanitarian and economic assistance, though the effects are not as dramatic—human suffering as opposed to battlefield movement.

The administration sent its FY 2024 budget proposal to Congress in March but did not include aid to Ukraine. Rather, the administration has waited until now because it has not been sure how long the war would last or what its nature would be. Waiting has indeed provided more clarity: the war goes on and at the same level of intensity.

Q3: How does this latest request fit into the aid that the United States has provided so far?

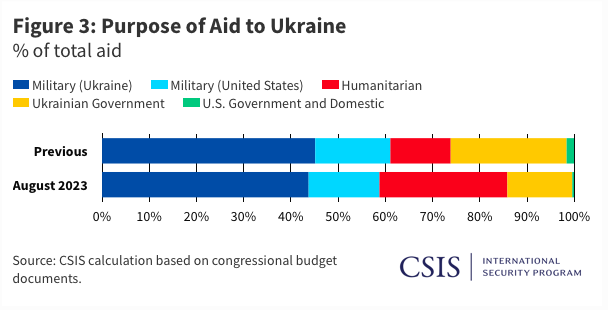

A3: CSIS has tracked aid to Ukraine from the beginning of the conflict, publishing analyses in May 2022 (“What Does $40 Billion in Aid to Ukraine Buy?”), November 2022 (“Aid to Ukraine Explained in Six Charts”), and February 2023 (“What’s the Future of Aid to Ukraine?”). Those analyses contain a full description of U.S. aid. Figures 2 and 3 below draw on these previous analyses to put the August request in context.

Figure 2 shows the total amount of aid enacted by Congress: $113 billion, which came in four packages appropriated by Congress: March ($14 billion), May ($40 billion), September ($12 billion), and December ($45 billion). The August package brings the total to $135 billion.

Figure 3 compares the purpose of the funding in the August package with the previous packages as percentages of the whole. The figure shows that the proportion of military aid has stayed about the same. The August proposal has relatively more humanitarian aid and less economic aid to the Ukrainian government.

Figure 3 compares the purpose of the funding in the August package with the previous packages as percentages of the whole. The figure shows that the proportion of military aid has stayed about the same. The August proposal has relatively more humanitarian aid and less economic aid to the Ukrainian government.

Q4: How long will this aid last?

Q4: How long will this aid last?

A4: This is an interim request. The expectation is that Congress will not have appropriations bills passed by the beginning of the fiscal year on October 1, so there will be a continuing resolution. This aid package will support Ukraine during the time of the continuing resolution. The administration will make another request when the appropriation bills shape up, likely in November or so. That was the pattern last year. The administration asked for enough money to get through the period of a continuing resolution. It later asked for money for the rest of the fiscal year.

The $113 billion of aid approved by Congress averaged over the 583 days of war between February 24, 2022, and September 30, 2023, comes out to $223 million per day or $6.8 billion per month.

Military aid to Ukraine has averaged $86 million per day or $2.7 billion per month. Thus, a $23 billion aid package will last about 100 days, the expected period of the continuing resolution. Indeed, the administration’s documentation sent to Congress cites three months in one program description (“Economic Support Fund” section of the administration’s August request).

Why not ask for a full year of funding now? There are three reasons. First, the administration does not want to ask for a large amount of money―for example, enough to last for the entire fiscal year―because that would generate a lot of attention at a time when the other appropriations bills are not being considered. It is less controversial to put Ukrainian aid funding into the context of the full federal budget when the final budget deal is being made. Second, a full-year funding at this point would imply that the war will continue for another whole year. That is not yet clear. Finally, the administration is unsure about the nature of the war—whether it will continue at the current high level or settle down to a long-term stalemate that entails a lower level of operations.

On the other hand, the administration does not want to ask for too little money and then go back to Congress repeatedly with all the political controversies that go with it. The two-step process, continuing resolution request and then a full-year request as part of the final budget negotiations, is a compromise.

Q5: Will political opposition reduce or even block this proposed aid funding?

A5: Blockage or reduction is unlikely, but a political battle is inevitable, given rising concerns on both the left and the right. Progressives want to use the money for domestic purposes and agonize about the suffering that war entails. The populist right wants to reduce federal spending and avoid foreign entanglements. In the House vote on the National Defense Authorization Act, populists got 70 votes in a failed attempt to strip out $300 million of Ukraine funding. So far, however, the opposition has not stopped or even reduced aid in the face of strong bipartisan support.

What is new is the disappointing results of the Ukrainian counteroffensive so far. Although the counteroffensive began two months ago, Ukrainian forces are still chewing their way through the Russian defensive lines. Even President Zelensky has acknowledged the disappointment. Frustration is building. The great fear is a “forever war,” a conflict that goes on indefinitely at a great human and fiscal cost but without a clear outcome. Ukraine has tried to ease these concerns and has urged patience. However, recent CNN polling in the United States shows a majority saying “the United States has already done enough” (51 percent) and “should not authorize additional funding” (55 percent).

Opposition to aid packages often manifests itself in support for immediate negotiations because they seem to offer a way to end the war without betraying Ukraine. However, given Russia’s recalcitrance, any deal will reflect the situation on the ground. Currently, that would be an armistice with Russia retaining the territories it still occupies.

Economic aid may be most vulnerable as conservatives tend to support military aid and progressives support humanitarian aid. By contrast, economic aid goes to the Ukrainian government. Some on the left and right will argue that U.S. local governments need the money more.

There may also be a push for additional oversight. Although the administration argues that oversight is extensive and no significant problems have yet arisen, this is always a sensitive area. Evidence of widespread abuses would be extremely damaging to outside political support. It is also an area where the administration and congressional skeptics may find common ground.

Q6: What happens next?

A6: The administration will push Congress to act on this aid package. Given the political difficulty surrounding any appropriations action, the package may be attached to the expected continue resolution. Since the continuing resolution is a “must pass” bill, that increases the chances of the aid package getting a vote. If there is a government shutdown, as some deficit hawks are pushing for, there could be a gap in funding. That will not lead to an immediate end of support since Ukraine will continue to receive equipment and supplies that are already in the pipeline. Because previous shutdowns lasted a few weeks at the most, a funding gap would probably stop any offensive actions but not be fatal to Ukrainian resistance.

In the longer term, Ukraine’s success on the battlefield will drive both the need for future aid packages and the political fate of those packages. With both near-term and long-term aid packages in play, the fall could be a time of crisis.

*

Mark F. Cancian (Colonel, USMCR, ret.) is a senior adviser with the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. During his time in the Office of Management and Budget his staff helped develop military aid packages for Eastern Europe and Ukraine.